2019 in Review | Year ends with Free Lula and Operation Car Wash in tatters

The justice system played a key role once again in the chess game of Brazilian politics in 2019.

The year started with ex-president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, from the Workers’ Party (PT), incarcerated in Curitiba, southern Brazil, while the judge who persecuted him, Sergio Moro, took office as Justice minister in the Jair Bolsonaro administration. But the case reached a turning point on June 9th, with a series of reports exposing private messages between the then judge and prosecutors, confirming the political bias behind the prosecution of the leftist leader.

The series of reports published by The Intercept Brasil showed the shady relationship between Moro and members of the corruption investigation and contributed to debase the task force. The leaks even spilled over to Supreme Court justices. The Car Wash task force chief prosecutor, Deltan Dallagnol, has not been able to properly refute the accusations, and neither have the Curitiba courts.

One of the most astonishing revelations made by The Intercept Brasil was that Dallagnol was trying to make a profit out of the fame he found as head of Operation Car Wash, devising a business plan to give high-priced talks about the investigations and even considering establishing a company under his wife’s name to avoid raising questions about his own activities. To top it all off, judge Moro unlawfully gave Car Wash prosecutors directions about how they should conduct the investigations and even how they should take the testimony of co-defendants who made plea agreements with the prosecution.

Concurrently, Car Wash prosecutors in Paraná state tried to close a billion-dollar deal with the United States to create a private foundation with public money from the Brazilian state-run oil company Petrobras. The Supreme Court barred the operation.

Persecution

The debasement of Operation Car Wash among public opinion did not start, nevertheless, with the series of exposés. In the first half of 2019, the persecution against Lula became clear in a number of ways, exposing the violations that have been committed since the beginning of the investigations, in 2009.

The courts refused to let the president grant interviews until April, even though the law allowed, and despite the numerous requests made by different media outlets.

In one episode, judge Carolina Lebbos argued that “the inmate is subject to a specific legal regime in which it is not possible, for reasons inherent in the incarceration, to assure him as much rights as those conferred on citizens who are fully enjoying their freedom.”

The argument was overturned by the president of the Supreme Court, Dias Toffoli, on April 18th, and Lula was finally allowed to speak with the media from prison.

Eight days later, he granted his first interviewed since he was incarcerated, to journalists Mônica Bérgamo and Florestan Fernandes Jr., with the newspapers Folha de S. Paulo and El País, respectively.

Another event that tarnished the image of the Car Wash task force was when the former leftist president was barred from attending his brother’s funeral.

Genival Inácio da Silva, known as Vavá, died in January after a battle with cancer, and while the Brazilian law establishes that inmates serving a prison sentence are allowed to attend funerals of family members, the Federal Police denied Lula’s request, claiming that they did not have the means or a team to escort the Workers’ Party leader from Curitiba to São Paulo.

Moreover, the Public Prosecutor’s office released a position paper underscoring “technical obstacles,” which led judge Lebbos to deny his request, arguing that it was not possible to “guarantee the ex-president’s physical integrity.”

The decision sparked such a huge backlash among Brazilians that authorities changed their ruling when Lula’s 7-year-old grandson Arthur died from a bacterial infection. Lula finally left prison for the first time in March, and was allowed to mourn with his family, but only for a few hours.

Presumption of innocence

In each of those episodes, large sectors of the Brazilian people resisted and expressed their support for Lula.

One of the most striking examples of this was the Free Lula Vigil, a camp set up outside the Federal Police building in Curitiba on the day Lula was incarcerated, and which remained active during the 580 days the ex-president was held in prison.

The camp held rallies, political education activities, and talks with political leaders from Brazil and abroad who visited the former president.

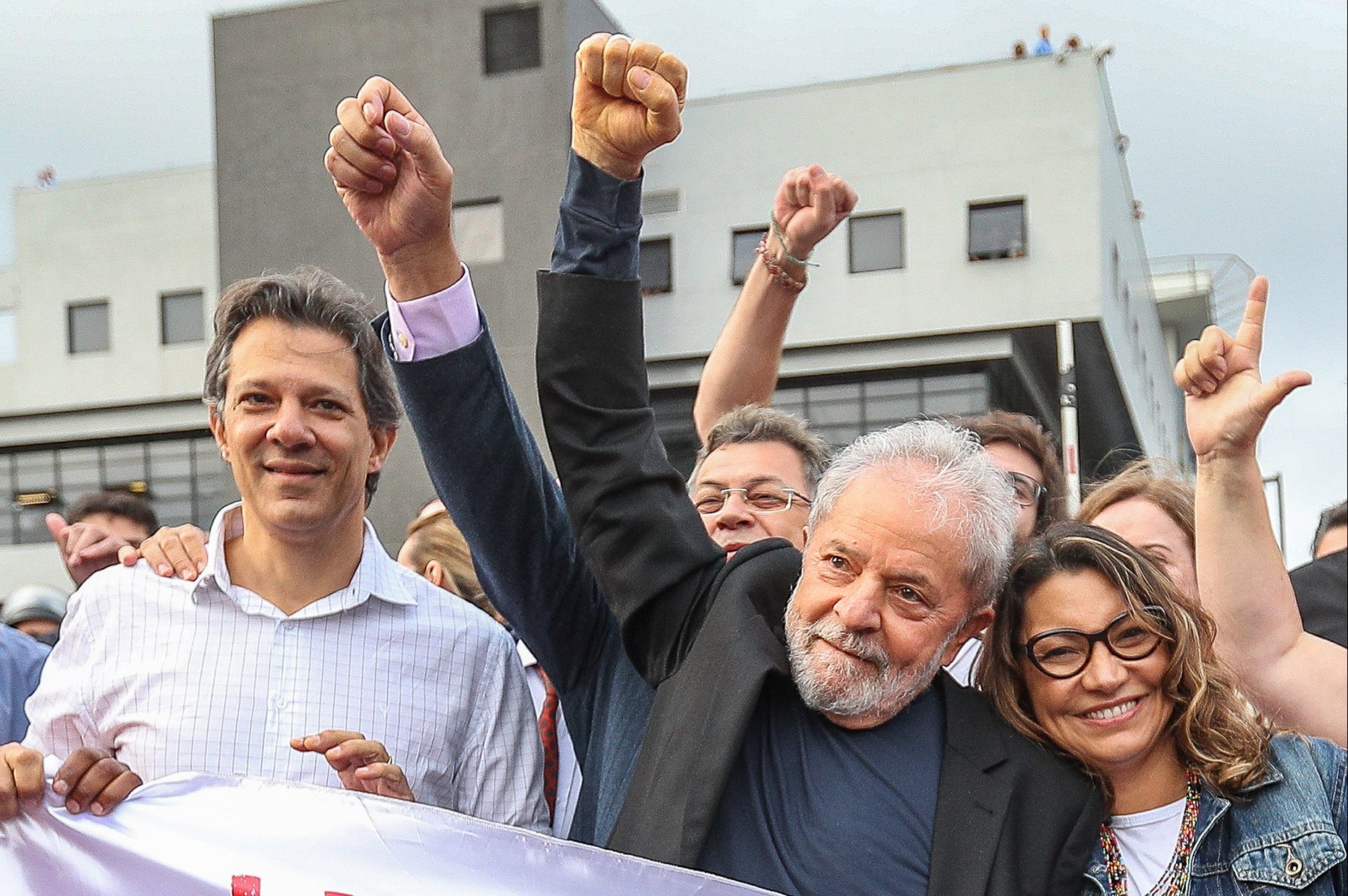

One of the first places Lula visited as soon as he left prison, on November 8th, was the Free Lula Vigil, after addressing the huge crowd of supporters who were waiting to welcome the ex-president out.

On the next day, he delivered a poignant speech outside the Metal Workers’ Union in São Bernardo do Campo, one of the organizations that has provided a solid bedrock of support for him throughout his political career.

“We cannot allow militiamen to destroy this country that we have built”, Lula said, referring to the Jair Bolsonaro administration. He also reiterated that he is willing to fight for justice.

Lula’s release from prison came after a Supreme Court ruling the night before, when the top court declared that a person convicted in a case can only be imprisoned after all possibilities of appeal are exhausted. The ex-president had been incarcerated after an appeals court upheld his conviction, but he is still filing petitions with higher courts.

Recent developments in 2019

In February, the former president was convicted in a new case. And while the series of exposés of Operation Car Wash seemed to have wrapped up by the end of 2019, the persecution against Lula had not.

In November, an appeals court upheld the sentence, disregarding the fact that the trial judge had simply copied and pasted the sentence from the case that originally led to his arrest, regarding a beachside apartment. The panel of judges also increased the length of his prison sentence in this case from 13 to 17 years.

The stories exposing the dubious relationships in the inner circles of Operation Car Wash have affected the approval ratings of Sergio Moro, the judge who tried Lula and later became Justice minister under Bolsonaro.

A poll by Datafolha Institute showed that the number of Brazilians who think the former judge is “excellent or good” dropped ten percentage points – from 63 to 53 percent – in December over April. Nevertheless, Moro was able to successfully push legislation as part of his conservative agenda, as Brazil’s Congress passed in December his so-called “anti-crime” package. Moro’s approval ratings are still higher than those of president Jair Bolsonaro.

While conservatism remains on the rise in the federal government, Lula’s release was welcomed as a victory for the Brazilian left in the run-up to the country’s 2020 municipal elections.

Lula’s freedom “changes the correlation of forces for the left,” the political scientist Armando Boito, of the State University of Campinas, told Brasil de Fato.

For the year to come, the former president plans to join the resistance against the Bolsonaro government. During an exclusive interview to Brasil de Fato days before his release, Lula said:

“I see Bolsonaro saying his nonsense, and [Economy minister Paulo] Guedes selling off Brazil. And we are carrying out this endless economy-driven struggle. But I think the struggle now is eminently political. They don’t have the right to sell Brazil off. We have to recover the Brazilian people’s rebellious spirit,” the Workers’ Party leader added.

Brasil de Fato | Edition: Vivian Fernandes